GEORGE W. THOMAS AND HERSAL THOMAS

George Washington Thomas

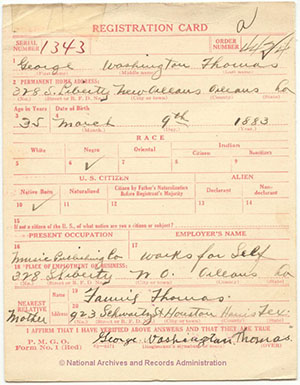

WWI Draft Registration Card

12th September 1918

George W. Thomas was an important figure in the national popularization of Texas blues in the late 1910s and 1920s. The music of George and his siblings Hersal, Beulah (’Sippie’) and his daughter Hociel carried the sounds of east Texas to New Orleans to Chicago and then to the rest of the country via the boogie-woogie pianists like Meade Lux Lewis and Albert Ammons; boogie-woogie in turn provided the heartbeat of the music which in the 1950s became known as rock and roll. Hence it has been argued [1] that George and Hersal Thomas were grandfathers of the pop music mainstream today.

George Thomas was the eldest son of George Thomas (March 1852(?)- 1917) [2] and Fannie Bradley[3] Thomas (Oct. 1865 [2] – 1922). George Sr. was born in Alabama of Alabama-born parents, while Fannie was born in Arkansas just after the Civil War. Fannie’s mother was born in Virginia, while at different times she reported her father as having been born in Africa (1900 Census) or South Carolina (1920 Census). Fannie and George Sr. married in Arkansas sometime around 1879 [2]; their first child was a daughter, Florence, born in June 1880 (evidently after 8 June, since her age at last birthday is given as 19 in the 8 June 1900 Census). George Jr., born March 9, 1883 [4], was the second-born Thomas child (at least to survive childhood). By 1910, Fannie told the census enumerator that she’d had 13 children, 8 of whom were alive in that year. Another son, John, born in January 1896 [2], had apparently died by 1910, but Fannie and George Sr. had had another son by 1910: Hersal, whose unusual given name was rendered by the enumerator as "Hearcile." Hersal had been born around 1906 [5].

The large Thomas family had moved from Arkansas to Houston, Texas between the birth of daughter Beulah (1 November 1898 [6], in Arkansas), listed by the enumerator in 1900 as "Bee", and the 8 June 1900 enumeration of the family in Houston. Beulah was later to be universally known by her childhood nickname "Sippie" when she became when of the most famous "classic blues" singers of the 1920s, mostly singing tunes composed by her older brother George and her baby brother Hersal.

The 1910 census shows George Jr. as a widower at the age of 27. Fannie is shown as being of the mother of 8 children living in 1910, yet two sons and seven daughters are listed in the household (along with a niece Marie and her husband Joseph Dormus and a lodger)! This apparent inconsistency does jibe with the widely-held view that Hociel (whose name was spelled "Hocile" by the enumerator; she is shown as having been born circa 1904, in agreement with the standard date of birth given in several sources as 10 July 1904) was in fact George Jr.’s daughter, but was raised by her grandmother Fannie as one her own daughters.

While 17-year-old George Jr.’s occupation in 1900 was given as ’salesman’, by 1910 he’d found his calling, as his occupation is shown as ’musician’ working for a ’show’. Clarence Williams reported having worked with George Thomas in Houston around 1911, when he wrote reminiscences of George Thomas as part of annotations to "Boogie Woogie Blues Folio" (1940), as quoted in [6,7]. Thomas was playing an instrumental number that he called "Hop Scop Blues" featuring a walking bass of broken octaves in the chorus. This tune was later published by George as "New Orleans Hop Scop Blues". It’s probable that Jelly Roll Morton met Thomas in Houston at around this time (1911), since Morton was working in the same theatrical circles in Houston in 1913 (see documentation by Gushee regarding Morton’s 1913 residence in Houston; Williams reported that he’d been ’playing vaudeville with the Benbow Stock Company’, and Morton toured with a Benbow company during the same period.) Probably Morton thought little of Thomas’s playing, classifying it in the category of "just ordinary blues — the real lowdown blues, honky tonk blues."

According to Clarence Williams, Thomas moved from Houston to New Orleans around 1914, and, inspired by his friend Clarence’s example, began to publish music there. Consistent with Williams’s statement, the census shows Thomas living in Houston in April 1910, while Thomas’s first publication listed in the Catalog of Copyright Entries, a song entitled "It’s Hard To Find A Loving Man That’s True", with words and music by G.W. Thomas, was registered for copyright on November 11, 1915 from New Orleans. Another early publication of George’s was his now-retitled "New Orleans Hop Scop Blues" (copyright 8 June 1916), with a lyric full of local New Orleans references. As discussed at length in [7], the appearance in print of a chorus that partially uses a walking bass of broken octaves in this tune is not a first – Artie Matthews’s "Weary Blues", published by John Stark in St. Louis the year before (1915), contains a full 12-bar blues chorus with the traditional chord sequence and a left hand entirely made up of a broken octave walking bass. Perhaps equally to the point, the alteration of a ragtime ’oom-pah’ left hand and an moving bass line in octaves, sometimes walking, sometimes struck together, was already characteristic of pieces published in Texas in the early ’teens. "Majestic Rag" by Ben Rawls and Royal Neel, published in 1914 by Bush and Gerts in Dallas, Texas is an excellent example, with a measure or two of pure broken-octave walking bass in the second strain and a varied and active left hand part throughout this bluesy rag.

Soon George branched out in his publishing to include tunes that others had written that he’d arranged ("Crawfish Rag" by Viva Celeste Seals, arranged G.W. Thomas, copyrighted 10 June 1918) or songs with lyrics by others ("Sweet Baby Doll", words by Wilbur Leroy, music by G.W. Thomas, published by Geo. W. Thomas, New Orleans, 3 February 1919), along with tunes, both instrumentals and songs, entirely by himself. "Houston Blues: A Southern Overture" is a tribute by George to his former city of residence, published by him on 8 September 1918. The copyright of "That Bullfrog Rag", an instrumental published by George in 1917 (copyright 23 February 1917, published 31 July 1917), was transferred to Williams and Piron later that year, perhaps an indication that indeed the friendship and business relationship between George and Clarence Williams were continuing to thrive in New Orleans. George even copyrighted an instrumental waltz entitled "Gert Anna Waltz (So Sweet)" on 22 January 1920, although evidently he didn’t consider the waltz to have sufficient commercial potential to publish it.

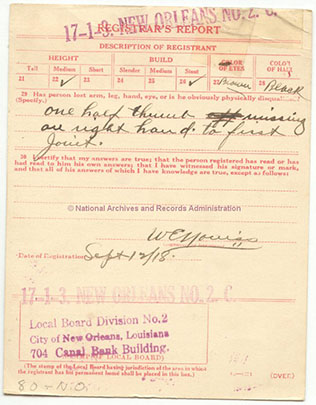

On 12 September 1918 George registered for the draft, listing his birthdate as 9 March 1883, giving his full name as George Washington Thomas, his address as 328 S. Liberty in New Orleans, and his occupation as music publisher, working for himself. He gives his mother as his nearest living relative (implying that George Sr. had died by this time) and her address in Houston. Most interestingly for a piano player, George claims disqualification for the draft due to his missing half of his right thumb! (Shades of Mamie Desdume!) This may account for the fact that there are no documented solo piano performances by GWT on record. (The solo recording of "The Rocks" [Okeh 4809-A, February 1923] attributed to ’Clay Custer’ on the label has often been credited to George Thomas, but, contrary to what has been stated in many places, there is actually no evidence that ’Clay Custer’ was a pseudonym for George Thomas. The player might have been Hersal Thomas, but the date seems early - see below. Hersal’s first documented appearance on record was not until two years later, in February 1925, when he was recorded by a field unit of Okeh in Chicago. The Okeh "Rocks" was recorded in New York [13 ], and interestingly the adjacent matrix number is a recording by the white pianist Harry Jentes of his novelty piece "The Cat’s Pajamas". Not that the style of Harry Jentes’s playing has much in common with the playing on "The Rocks"!)

The Texas Death Index 1903-1940 shows four individuals named George Thomas as dying in Harris County Texas in the 1915-1918 period prior to George Jr. ’s draft card date, and one George W. Thomas dying on 26 July 1917 (file 19391). Perhaps the latter is the most likely subject for further investigation. From the dates and counties of death listed for any of the six (!) individuals listed explicitly as ’George Washington Thomas’, none of them seem to be plausible candidates for GWT’s father. Note added (2017): over the past year, death certificates for Texas covering this period have become available. Indeed, the speculation that the George Thomas that died 26 July 1917 was in fact George Washington Thomas Sr., father of the musicians, turns out to be correct. The death certificate shows that George and Hersal's father died at home in Houston; George Jr. gave his father's age at death as 51 years old, which seems too young and disagrees with the year of birth given by George Sr. to the census enumerator in 1900. The certificate also indicates that George Sr. was buried in Evergreen Cemetery, in the 5th Ward. No marker exists on the grave and unfortunately burial records for this historic cemetery do not survive today.

George was still living at the address that he’d listed on his draft card on 14 January 1920, when he appears in the 1920 census as a 35-year-old (actually he would have been 36 at his last birthday) boarder at that address. He gives his occupation as "musician", and lists his marital status as single, not widowed or divorced. Meanwhile, George’s mother Fannie still lived in Houston at the same address that George had listed on the draft card (923 Schwartz) [8] with her daughters Willie and Myrtle and her young son Hersal, whose age is now given as 12, two years younger than would be extrapolated from the 1910 census entry. This census information contradicts the interview Sippie Wallace gave to Daphne Duval Harrison late in her life [9], in which Sippie stated that both her parents had passed away by 1918, at which time she returned to Houston. On the other hand, Sippie had told Ron Harwood years earlier that her mother had died in 1923, "probably in the summer" [10]. I have located the sole Fannie (or Fanny) Thomas listed in the Texas Death Index 1903-1940 as having died in Harris County, Texas in the year range of interest as passing away on 27 January 1922 (file number 1810); whether this is George and Sippie’s mother will be a matter for further research. Note added (2017): again, this speculation proved correct. Fannie's death certificate shows that she died of kidney failure; again, her age as given by her daughter Lucy is too young to be mother of her eldest children and disagrees with the census data. Fannie was also buried in Evergreen Cemetery, presumably adjacent to George Sr.

George’s friend and mentor in the music publishing business Clarence Williams moved from New Orleans to Chicago by February 1919 [6], and soon thereafter George did likewise. The earliest copyright to show a Chicago address for George is "I Can’t Be Friskey [sic] Without My Whiskey", words by W.E. Hunter and music by GWT, copyrighted 21 August 1920, so he relocated between 29 January 1920 (copyright of "I’ll Give You A Chance To Make Good" received from New Orleans) and that date. An instrumental entitled "Muscle Shoals Blues" which originally George had copyrighted but not published (copyright 8 February 1919) was among George’s early Chicago publications. Outfitted with a characteristically awkward lyric by himself, George published it on 29 August 1921 and it appears to have been something of a hit. The QRS piano roll of the tune, number 1888, was played by James P. Johnson and was released in April 1922. On 21 October 1922, Johnson’s 18-year-old protégé Thomas ("Fats") Waller recorded the tune for Okeh (released as OKeh 4757-A) [11] as a piano solo in a style quite similar to his mentor’s roll, as his first record.

Perhaps the two most famous tunes by George Thomas today are "The Rocks" and "The Fives", because the titles of these two tunes reportedly became associated with specific left hand boogie-woogie patterns among Chicago pianists, though those particular patterns do not appear in the original versions of Thomas’s publications. Nonetheless, by all accounts these two tunes were highly influential among the young blues pianists in Chicago in the early 1920s. George copyrighted "The Fives" as an unpublished composition on 9 December 1921 (copyright deposition p. 1, p. 2, and 3), giving composer credit to his young brother Hersal and himself, and credit for the lyric to himself. It seems unlikely that Hersal had moved to Chicago by this date, as probably that did not occur until after Fannie’s death. Hence Hersal and George may have collaborated on this tune during a visit by one brother to the other’s home. The left hand part is a mixture of different patterns, rather than the consistent use of a single figure that became the norm in later boogie-woogie. A comparison between the manuscript deposited to establish the copyright and the version George published the next year shows a number of interesting differences. The phrases in the chorus have been extended by three bars so that the chorus consists of a repeated 11 bar structure, instead of the more usual 8 bars of the manuscript version. Also, the rhythm of the main figure in the chorus has been changed in an important way. The W.W. Kimball Co. of Chicago issued a piano roll of "The Fives" without a credited player; the roll was based closely on the published version of the tune (not the manuscript version). The noted piano roll authority Mike Montgomery speculates that Thomas might have commissioned Kimball to issue the rolls of his tunes (the cover pages of the published "Fives" and of "The Rocks" both state "Player Piano Rolls and Records Ready"), and given the roll arranger the published sheet to work from. However, the roll of "The Fives" includes an interlude between literal repetitions of the verse and chorus that is not in the published sheet music. In fact, this unpublished section sounds more like what would soon be called "boogie woogie" than the published part of the tune. It is quite likely that George wrote this section out for the roll arranger, as George included a similar instrumental interlude in the published version of "Shorty George Blues", marked "This Dance Part can be omitted. But if you Play it, it will be interesting"! In fact, the latter half of the interlude in the "Fives" roll is almost identical to the chorus of "Shorty George". Though the Kimball company listed these rolls of Thomas tunes in their catalog, they are exceedingly rare, and in fact Montgomery never found a copy of the Kimball roll of the other George Thomas hit "The Rocks" (1922). However, upon publication of this essay, it emerged that the New Zealand roll collector Robert Perry has a copy of this Kimball roll in his collection!

The essential riff of "The Fives" is closely related to the chorus of the traditional jazz tunes "Tin Roof Blues" (New Orleans Rhythm Kings) and "Jazzin’ Babies Blues" (Richard M. Jones). Though the first appearance of the latter two tunes on records is demonstrably later than the copyright of "The Fives", several sources claim that this was a riff used by New Orleans musicians well before these early twenties recordings. Perhaps we can conclude that the riff is a southern folk strain, rather like the relationships between "Buddy Bolden’s Blues" and "St. Louis Tickle", or between the main strains of "Wild Cherries Rag" (Ted Snyder), "Carolina Shout" (James P. Johnson), "Buddy’s Habit" (Charley Straight), "Little Rock Getaway" (Joe Sullivan), etc.

The biggest piano roll making concern, QRS, had its blues specialist J. Lawrence Cook arrange versions of both "The Fives" and "The Rocks" a few months after hiring Cook - the two rolls are numbers 2370 and 2371 in the word roll series and were issued in September 1923 (Cook started working exclusively for QRS in May of that year). One of these arrangements was issued as credited to Cook, and the other credited to his "Sid" Laney pseudonym. Later, Cook arranged rolls of other Thomas tunes: "Underworld Blues" (QRS 2799, September 1924), "Caldonia Blues" (QRS 2810, also September 1924), "I Keeps My Kitchen Clean" (QRS 4006, August 1927), and "Dead Drunk Blues" (QRS 4292, June 1928). Curiously, QRS seems not to have issued a word roll of "New Orleans Hop Scop Blues"[12], even after the copyright was taken over by Clarence Williams in 1923 and, predictably, plugged aggressively by Williams.

George Thomas himself is listed as the player on only a few rolls on the U.S. Music label. These include "Shorty George Blues" (US 41881, ?), "Caldonia Blues" ( US 42255, October 1924), "Washwoman Blues" (US 42563, January 1925) – all are tunes written by George in collaboration with his sister Sippie or his brother Hersal. Hersal is the named artist on only a single roll, also on the US label: "Underworld Blues" (US 42240, ?), on which his first name is misspelled as ’Hershel’.

One may speculate that Hersal moved to Chicago to be with his much older brother George after his mother Fannie’s death. George and Hersal’s sister Sippie were definitely in Chicago in October 1923, but if Hersal was also in Chicago by that date, he was not yet sufficiently an accomplished pianist to accompany his sister on her first record date. On Sippie’s first recordings, of the Thomas’s tunes "Shorty George Blues" and "Up The Country Blues", issued on Okeh 8106 and recorded in Chicago in October 1923 [13], the piano accompaniment was provided by Eddie Heywood [Sr.]. In the same sessions, Heywood accompanied other singers as well. (Interestingly, the same set of field recordings in Chicago that October included Jelly Roll Morton’s Jazz Band on "London Blues" and "Someday Sweetheart", issued on Okeh 8105.)

Just two months later, George accompanied a vocalist named Tiny Franklin in a session at the Gennett studio in Richmond, Indiana. They recorded two of the same tunes that Sippie had recorded ("Up The Country" and "Shorty George") and four other George Thomas tunes which George had copyrighted and published over the previous few years. (A detailed comparison of George’s playing on these sides, four of which were issued, with the playing of "Clay Custer" might help resolve whether "Custer" is in fact George Thomas, but would take this essay too far afield.) This kind of aggressive plugging of his copyrighted material is something that perhaps George had learned from his friend from New Orleans days, Clarence Williams. By this point, Williams had bought the copyright of George’s "New Orleans Hop Scop Blues" and republished it in New York in an edition with a modified set of lyrics (9 October 1923) and proceeded to similarly plug the tune by having it recorded by Bessie Smith.

Hersal Thomas’s first appearance on record is his solo of "Suitcase Blues", recorded by Okeh in Chicago in February 1925, released as Okeh 8227. He also accompanies his sister on the same date on three tunes, on which the siblings are joined by Joe "King" Oliver on cornet. In a session recorded in May 1925 in Chicago, Hersal accompanies his niece (older than he!) Hociel on two tunes as well as recording his other famous piano solo, the self-titled "Hersal Blues", which was released on the other side of Okeh 8227. It is clear from later reminiscences of Chicago pianists like Albert Ammons that Hersal Thomas made a strong impression on the other local pianists around 1925, as discussed in detail by Tennison [7].

Presumably while on tour, Hersal and Sippie made four sides for Okeh in New York in late August 1925; Hersal’s other recordings (accompaniments for Sippie or Hociel) for Okeh were all made in Chicago, the last such session being recorded on 3 March 1926, where Louis Armstrong joined Hersal and Sippie for three sides to add to the three the trio had made two days previous. Unfortunately, Hersal died suddenly in Detroit of food poisoning on 2 June 1926. The Chicago Defender for Saturday 12 June 1926, part 1, page 7, column 6: "Hersal Thomas, brother of Sippie Wallace, died of ptomaine poisoning in Detroit, Mich., June 2. The best of medical attention was given him by his wife, sister and other relatives, but of no avail. The body was shipped this week to Houston, Tex., accompanied by relatives." A remarkable aspect of the Defender account was the mention of Hersal’s wife. This is the only known source that mentions Hersal’s having been married (by twenty years of age). On the other hand, the Michigan death certificate shows Hersal as having been single, with the information having been provided by Sippie herself. Sippie also gave Hersal's date of birth as September 9, 1906, which is consistent with the 1910 census entry, and this date of birth makes Hersal 19 years old at the time of his death. Cause of death is given as "acute gall bladder". In a much later interview [10], Sippie’s recollection was "We never did find out exactly what it was gave him the poisoning, but we think that it was a can of pork and beans he had." In the same interview, Sippie gave the date of her brother’s death incorrectly as 3 July 1926, which has been picked up by almost every subsequent account of Hersal’s brief life. In fact, two weeks after Hersal’s death, George was inspired to write a song memorializing his brother entitled "They Needed A Piano Player in Heaven So They Sent For Hersal", which was copyrighted on 16 June 1926. Given the Defender item stating that Hersal's body was shipped to Houston for burial, it is reasonable to speculate that he was buried in Evergreen Cemetery near his parents. Unfortunately, the subsequent history of Evergreen Cemetery would suggest that the location of Hersal's grave will probably never be known or marked.

By her own account, Sippie’s interest in her performing career dropped off sharply after her brother’s sudden death, and by the late 1920s she had ceased performing in public. George, on the other hand, continued to be active in the music business for several years, recording a couple of his recent tunes on 14 July 1926, only a few weeks after Hersal’s funeral. George accompanied singer Ethel Bynum on "Rest Yo’ Hips", which George had copyrighted a few months previous (6 May 1926), and on "Bed Room Blues". The latter tune was deposited for copyright two days after the recording session, with lyrics credited to the singer. Perhaps Ethel had come up with the lyrics in the recording studio. Unfortunately, this pair of sides went unissued. Two years later (24 April 1928), George returned to the Gennett studio with another vocalist, this time Lillian Miller, to record some more of George’s tunes, including recent compositions ("Butcher Shop Blues", copyrighted 4 April 1928) and one of the earliest tunes he had published back in New Orleans ("You Just Can’t Keep A Good Woman Down," published 24 January 1916). Of the five tunes Miller and Thomas recorded that day, four were issued.

George’s songwriting career, as judged by the number of entries in the Catalog of Copyright Entries in his name, peaked in 1924 with 14 copyrights. In 1926, George copyrighted 11 songs, in 1927, 8. In 1928 and 1929, he copyrighted only two tunes in each year, and in the latter year, both copyrights were not on behalf of his own publishing company, but J. Mayo Williams’s State Street Music Publishing Co. In 1930 through 1935, George Thomas’s name does not appear in the Catalog of Copyright Entries.

But in December 1936, Thomas copyrighted a tune entitled "I Don’t Love Nobody But You; song", with the Catalog of Copyright Entries reading "1 c. [meaning that it was an unpublished work], Dec. 17, 1936; E unp. 136701; Geo. W. Thomas, Chicago." The reason that this entry is remarkable is that most of the dates given for George’s death, in all cases presumably stemming from recollections at different times by Sippie, predate this by up to eight years!

The mystery of exactly when and where, and under what circumstances, George W. Thomas died is solved by the Illinois death certificate (which I found around 2006). It shows that George Thomas, resident at 3143 Indiana Ave., Chicago, IL, died on March 6, 1937, of a broken back ("Fractured cervical vertebra with laceration of the spinal cord"), caused by the "deceased [having fallen] down steps". The informant, one Eddie [? - last name illegible], a neighbor at 3147 Indiana Ave., wasn’t aware of much personal detail about George, in that he gives George’s age as "about 43" (a significant underestimate, in that George was just days short of his 54th birthday at the time of his death), without a guess as to the date of birth, didn’t know who George had been married to, stated that George had been born in Houston, Texas (incorrect, but he had come to Chicago from Houston), and the informant had no knowledge of Thomas’s parents. He stated that George was a "music writer", that he was self-employed, and that he had spent "about 20 years" at this occupation. George Thomas was interred at Restvale Cemetery, Alsip, Illinois on March 10, 1937 in an unmarked grave (Section 1B, Row 1, Grave 34, interred March 10, 1937). The much more famous (today) Clarence "Pine Top" Smith, who is often considered the first person to record a boogie-woogie piece, in 1928, is also buried in that cemetery, and his grave has recently received an appropriate monument [14].

It seems highly unlikely that Thomas’s fatal fall down the steps was caused by ice or snow, since it appears that the weather in Chicago in early March 1937 was unseasonably warm and snow-free, with the high temperatures reaching around 60 deg F and no snow reported on the ground that week [15].

It seems the source of incorrect information both on the date of Hersal’s death (placing it on July 3, 1926 instead of the correct June 2) and of the date and particulars of George’s death (placing it variously in 1928, 1930, and 1937, in different cities!) was interviews that the brothers’ sibling Sippie Wallace gave late in life, to her friend and manager Ron Harwood [10] and to Daphne Duval Harrison [9]. The tale of Sippie’s return to public performance is a fascinating one, and Ron Harwood’s book with John Penney on the subject has been promised as forthcoming for many years as of this writing, most recently on the website http://www.sippiewallace.com/about-us/. Because of Sippie’s successful public career revival post-1965, inspired almost entirely by Harwood’s efforts, when she passed away on Nov. 1, 1986, her grave in Trinity Cemetery in Detroit is marked with a beautiful monument [16].

A most unfortunate aspect of George’s accidental death in 1937 was that he *almost* lived long enough to have enjoyed the tremendous revival of interest in boogie-woogie and blues piano styles that began to gather momentum in the year of George’s death and took off after the triumphant "From Spirituals To Swing" concerts in Carnegie Hall, produced by John Hammond, the first one being on Dec. 23, 1938. The popularity of the music of Albert Ammons, Meade Lux Lewis and Pete Johnson that ensued would have likely led to late-career success for George Thomas had he lived another couple of years. Lewis and Ammons consistently referred to the Thomas brothers as having been among their most important influences in their formative years in Chicago, and in the folio "5 Boogie Woogie Piano Solos by All-Star Composers" (Leeds Music Corp., NY, 1942) included an arrangement of "The Fives", with composer credit correctly being given to George and Hersal Thomas, editor Frank Paparelli’s note at the head of that arrangement read as follows:

"Albert Ammons and Meade ’Lux’ Lewis claim that ’The Fives,’ the Thomas brothers’ musical composition, deserves much credit for the development of modern boogie woogie. During the twenties, many pianists featured this number as a ’get off’ tune and in the variations played what is now considered boogie woogie. This is the first appearance in print of this composition."

Although the last sentence is incorrect, because George had published "The Fives" in Chicago in 1922, the recognition of the importance of the Thomas brothers to the development of blues and boogie woogie piano styles was finally being recognized publicly, only a few years after George’s obscure death in Chicago. We can hope that soon George’s grave in Alsip, Illinois can be graced with a proper monument, and that Hersal’s grave can be located and also memorialized.

Author’s note:

This article was originally commissioned by my late friend Mike Meddings (1939-2013), of Rugeley, England, around 2006, as part of the series of WWI draft card essays on his website doctorjazz.co.uk. Mike provided the color photographs of George Thomas’s draft card and the inspiration to dig into the details of Thomas’s life. Soon the essay grew beyond the bounds of the short pieces on Mike’s website, so we gave up on the idea of putting it on the site, especially since no firm evidence of a direct connection between Thomas and the main subjects of Mike’s website, Jelly Roll Morton and J. Lawrence Cook, could be found. (The attempt explains the mentions of Morton and Cook in the essay.) Some information was provided to me in telephone conversations with Mike Montgomery (1934-2011); Montgomery congratulated me when I obtained an original of the single piano roll that is credited to Hersal Thomas as a player (Underworld Blues, US 42240), saying that now I was complete on at least one of ’our guys’! I last worked on the essay in 2009 before other pressing issues caused me to set it aside for the moment. This year, Bill Edwards turned his attention to the Thomas brothers and published his detailed essay on his well-researched and indispensable website ragpiano.com . However, Bill had not located some of the sources I had been fortunate to find a decade ago, so it seems appropriate to publish the essay and exhibit some of the material. In particular it seems important to publicize the correct dates of Hersal’s and George’s deaths. I appreciate Bill’s efforts and had it not been for his tireless work as inspiration, I probably would have continued to have set this aside for another decade or two. - Bob Pinsker, San Diego, CA, July 15, 2016.

2006-2016 Robert I. Pinsker

|